Introduction

The electricity production ecosystems all over the world are changing rapidly.

The introduction and growing scalability of new technologies is driving change in an industry that has been doing business as usual for the past four to five decades.

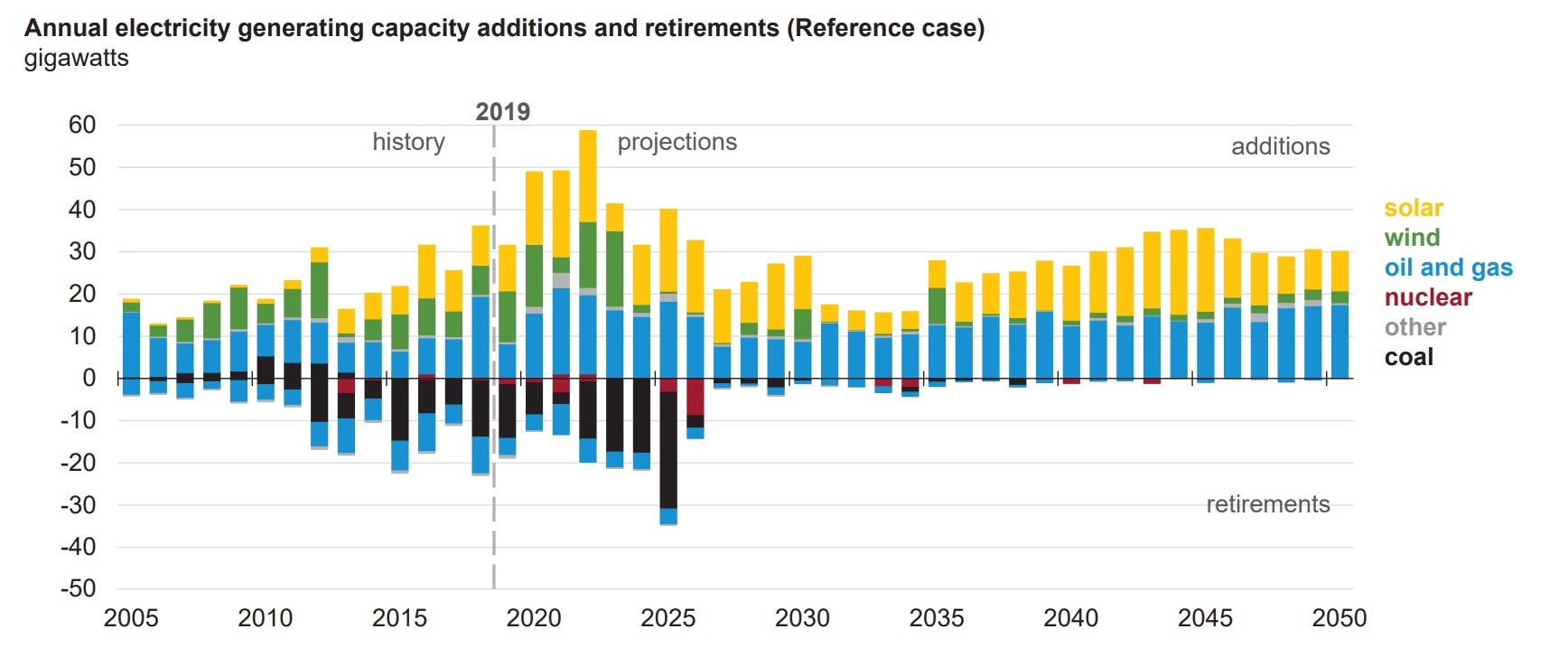

From the supply side of the industry, the companies providing the primary power production assets to the electricity producers and servicing these assets are facing new challenges. Before addressing these challenges, we will review how the power mix is evolving, both in terms of new assets to replace old, retired powerplants and how the service models work for these assets.

NEW BUILD

RENEWABLE ENERGY SOURCES

Renewable energy sources, primarily wind and solar, are continuing to gain newbuild market share across the globe. Support from government policies such as tax credits, grants, and emission trading certificates has enabled renewable power generation to reach a level of maturity and volume where projects can be economically viable regardless of public subsidies.

The intermittent nature of their generation profile does not, however, allow a system primarily based on renewables to match energy supply to energy demand at all times, which leads to a strong requirement for storage technologies to be developed and scaled up.

Utility-scale battery energy storage systems rated over 20 MW and lasting several hours are becoming increasingly common in various parts of the world. Furthermore, there are the first moves towards developing large-scale, “seasonal” energy storage projects, utilizing green hydrogen. Green hydrogen is produced by electrolysis, using excess renewable electricity, with the hydrogen then stored in large salt caverns. This can then be used in large, combined cycle gas powerplants to deliver electricity when needed.

COMBINED CYCLE GAS POWER PLANT

Combined cycle gas power plant, the most efficient of the fossil-based power production technologies, has been the dominant new-build option (where gas is economically available) for the last several decades. With the increasing shift to renewable sources, the demand for new combined-cycle gas power plant capacity has dramatically reduced. Whilst there will be a continued demand for these high-efficiency power plants, the annual volumes will be considerably lower than enjoyed in the past decades. The above-mentioned hydrogen projects will create some renewed demand but there will be a balance of hydrogen-capable new-build plus retrofit of existing assets to meet this demand.

CONVENTIONAL COAL-BASED TECHNOLOGIES

gas is not readily available, existing coal-based assets will continue to be deployed, creating a coal + renewables mix in countries such as China and India. Project financing for new-build coal-based projects is becoming increasingly more difficult to set up and as a result of the continuing low demand, a number of OEMs, including GE, Siemens Energy, and Toshiba, have declared the cessation of

supplying equipment for future projects.

Globally, government policies are to move away from coal as it is seen as “dirty;” however, where it is allowed, the drive is towards more efficient boilers and higher steam temperatures helping to drive down operating costs and CO2emissions but even this is aggressively challenged as a viable option – carbon-capture and storage/reuse is the only remaining option to keep coal in the energy mix but this is prohibitively expensive to implement.

DISTRIBUTED POWER

Distributed power covers a vast range of small-scale power generation technologies used both in front-of-the-meter and behind-the-meter applications. For the purposes of this discussion, the focus is on this type of asset that is also connected to a central grid distribution system to enable selling excess power produced.

SERVICES

TRADITIONAL SERVICE

Traditional service support for the power generation assets described above has

been focused on the major components or products in each asset group—the turbines, boilers, generators, etc. at the core of the power plant. The supporting systems and the infrastructure of the power plant itself have largely been managed by the plant owners or operators.

As the dynamics of the industry continue to change, assets have been and will continue to be divested and re-purposed to serve the changing market requirements. This will create the opportunity for existing and new supply-side companies to develop and offer broader, outcome-driven service packages to owners and operators who are simply less experienced in running such assets.

The key to all these asset types is to ensure that they are available to dispatch precisely when there is a demand for the electricity that they produce, within the economic framework the assets operate within. The changing mix of assets and the resultant increasing competition for dispatch drives the need for new, improved levels of service support to maximize plant real-time operating efficiency, better plant demand response characteristics, and overall smarter fleet asset management systems.

All these customer requirements will be achieved through the digitization of the whole system, covering both supply-side (addressed here) and demand-side response and management. The first steps have already been seen—the major OEMs have focused heavily on smarter equipment monitoring technologies, linked to digital tools which can handle the vast quantities of data generated, all aimed to better understand and ultimately utilize the asset in question. This is, however, only the beginning of this journey. The potential for broader digital asset and fleet management systems is enormous and coupled with artificial intelligence, these systems will transform the electricity production and delivery industry to yet unforeseen levels of productivity

THE SUPPLY-SIDE DILEMMA

These changes in the power industry’s dynamics will continue to have dramatic impacts on the major equipment suppliers.

SUPPLY-SIDE OVERCAPACITY

Supply-side overcapacity. Both General Electric and Siemens are being forced tore-size their Power divisions, each having seemingly failed to recognize the pace of renewable penetration and the resultant impact on new gas turbine order volumes. The number three contender in new gas turbine order volumes in the past, Mitsubishi Power, has become the leading contender over the last eighteen months, being less impacted by resizing and better organized to respond to change faster.

MORE DIGITAL INFRASTRUCTURE

power industry to function effectively with the changing mix of production assets, the volatility of the fastest-growing asset base, and the increasing need for equipment demand-side efficiency improvements. This area provides the greatest opportunity for new entrants to bring new technologies and different thinking to a very traditional, static industry.

OEM LOYALTY?

OEM loyalty? Traditionally owners and operators have relied on the equipment OEMs to provide lifecycle service support. Is this approach relevant for the future? The challenge for the OEMs is to reinvent themselves quickly to fit in the new, rapidly changing ecosystem—where not only have they to be relevant but also provide a better value-added offering to differentiate beyond the alternative service contenders.

NEW TECHNOLOGIES

New Technologies. Technology is at the core of the change occurring in the industry. Offshore wind turbines are currently in the “scaling race;” all the major OEMs are developing higher output machines—now moving into the 12-15 MW range. Offshore wind is gaining more interest and as new build programs scale up there are engineering and supply chain opportunities to serve the production of these products as well as the construction and lifecycle support of this next wave of renewable technology. The role of environmental pressure groups and government policies will have an impact on those technologies that come to the fore.

Energy storage, particularly battery energy storage, is another technology gaining commercial scale to support the growth in volatile renewable energy production and support short-term grid stability. Equipment costs and installation costs continue to fall as deployment increases.

Hydrogen is increasingly being considered as an option for longer “seasonal” energy storage. Although still relatively new, this development has the potential to accelerate the global drive to net-zero emissions.

The opportunities for digitization and use of artificial intelligence in managing the production base along with the demand side, e.g. regulating power taken by industrial users through interfacing with their processes are enormous and currently are only at the early deployment stage. Could this be the Airbnb for the power industry?

TRADITIONAL TECHNOLOGIES

Traditional Technologies. All the energy production assets discussed are designed to produce electricity for long periods—product lifecycles typically range from twenty to more than forty years. Much of the focus tends to be on the new technologies but electricity will continue to be produced from the existing installed assets for several decades, even in regions such as North America and western Europe where the new build of “old” technologies has ceased.

SUMMARY

ENERGY TRANSITION IS GAINING MOMENTUM

The energy landscapes continue to redefine themselves with increasing momentum across the globe. The use of coal as a fuel source to produce electricity is increasingly being recognized as a significant challenge – further pressures in terms of non-availability of project funding for new-build coal projects is adding further pressure; as a result, major equipment suppliers are discontinuing production for new-build.

This, however, is only part of the challenge; the installed base of coal assets is still substantial and will need to be cleaned-up (carbon capture & storage/reuse) or their retirements accelerated. Offshore wind is growing rapidly, with the major equipment suppliers pushing the scaling of their turbines into mid-teen MW output levels. Coupled with the increasing use of short-term battery-based energy storage and longer-term “seasonal” green hydrogen energy storage, there is now a technology roadmap to create net-zero emissions electricity production future.

Whereas a few years ago the OEMs on the supply side of the industry were“blindsided” by the pace of the renewables build-out, the majority have regrouped, right-sized their operations, and are now gearing to serve this new model.